Building a Data-Driven Complaint Triage Agent with DSPy and Databricks

At Casper’s Kitchens, our ghost kitchen network handles hundreds of food delivery orders daily. With volume comes complaints—late deliveries, missing drinks, soggy fries, and more. Each complaint needs a response, and ideally, a fair resolution.

Manual triage is slow and inconsistent. Simple keyword-based automation makes arbitrary decisions without understanding context. What we needed was an agent that could make defensible, data-backed decisions at scale: one that returns structured outputs, uses real order data to justify decisions, and can be deployed, monitored, and improved over time.

While Casper’s is a demo project, this agent implementation represents patterns we’d use when prototyping an agent for production use. In this post, I’ll walk through how we built a complaint triage agent using DSPy and Databricks.

Why DSPy?

DSPy is a framework for building language model applications with a focus on structured programming rather than prompt engineering. Instead of crafting elaborate prompt templates and managing tool-calling logic manually, you define typed interfaces (called “signatures”) and let DSPy handle the orchestration.

For our complaint triage agent, DSPy offered several advantages:

- Concise, readable code. DSPy signatures replace verbose prompt templates with Python classes that declare inputs, outputs, and instructions. The result is code that’s easier to understand, test, and maintain.

- Composable, model-agnostic architecture. DSPy’s abstractions make it straightforward to evaluate the same agent logic across different models from different providers. By changing the model configuration, we can compare Claude, GPT, Llama, Gemini, and others without rewriting agent code. This makes it easy to find the right balance of quality, latency, and cost for your use case.

- Straightforward Databricks integration. DSPy plays nicely with Unity Catalog functions (our data retrieval layer), Databricks Model Serving (deployment), and MLflow (tracing and evaluation). Everything stays in the Databricks ecosystem, which simplifies operations and governance.

Other frameworks like LangChain, LlamaIndex, or the OpenAI Agents SDK work well for building agents too. We chose DSPy for this project because its declarative, signature-based approach aligned with our preference for structured, testable code.

What the Agent Does

At a high level, the complaint triage agent automates the initial assessment of customer complaints. When a complaint comes in, the agent:

- Retrieves order data by calling Unity Catalog SQL functions that query our order database for delivery timing, item details, and location-specific benchmarks

- Analyzes the complaint against this real data—comparing actual delivery times to percentiles, verifying claimed missing items against the order, checking food quality issues against severity patterns

- Makes a decision: either suggest a specific credit amount (with confidence level) or escalate to a human reviewer (with priority)

- Provides a rationale citing the specific evidence that supports its decision

A typical output looks like:

{

"order_id": "4394a1bca54c4ddf963e51e",

"complaint_category": "missing_items",

"decision": "escalate",

"credit_amount": null,

"confidence": null,

"priority": "urgent",

"rationale": "Order marked as delivered without customer receipt indicates potential fraud or logistics failure..."

}

This agent isn’t a customer-facing chatbot. Instead, it’s part of an automated data pipeline: complaints flow in (from forms, emails, support tickets), the agent processes them, and its structured outputs feed into downstream systems, auto-crediting approved amounts, routing escalations to support staff, logging decisions for audit trails.

The value is consistency and speed. Every complaint gets evaluated against the same data-driven criteria, and the agent’s pre-screening saves customer support critical time.

Agent Architecture

Now let’s walk through the complaint triage agent’s core components. The full implementation is available in this notebook, but I’ll highlight the key pieces here.

The Signature: Defining the Agent’s Interface

In DSPy, a Signature defines what your agent does: inputs, outputs, and instructions. Here’s our ComplaintTriage signature (condensed for clarity):

class ComplaintTriage(dspy.Signature):

"""Analyze customer complaints for Casper's Kitchens and recommend triage actions.

Process:

1. Extract order_id from complaint

2. Use get_order_overview(order_id) for order details and items

3. Use get_order_timing(order_id) for delivery timing

4. For delays, use get_location_timings(location) for percentile benchmarks

5. Make data-backed decision

Decision Framework:

- SUGGEST_CREDIT: Compare delivery time to location percentiles, verify missing items

- ESCALATE: Vague complaints, legal threats, health/safety concerns

Output Requirements:

- For suggest_credit: credit_amount (required), confidence (required)

- For escalate: priority (required)

- Rationale must cite specific evidence

"""

complaint: str = dspy.InputField(desc="Customer complaint text")

order_id: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="Extracted order ID")

complaint_category: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="EXACTLY ONE category: delivery_delay, missing_items, food_quality, service_issue, billing, or other")

decision: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="EXACTLY ONE: suggest_credit or escalate")

credit_amount: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="If suggest_credit: MUST be a number (e.g., 0.0, 10.5). If escalate: null")

confidence: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="If suggest_credit: EXACTLY ONE of high, medium, low. If escalate: null")

priority: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="If escalate: EXACTLY ONE of standard or urgent. If suggest_credit: null")

rationale: str = dspy.OutputField(desc="Data-focused justification citing specific evidence")

The signature’s docstring becomes the agent’s instructions. We embed our business logic, such as when to offer credit, how to categorize complaints, and what evidence to cite, directly in this description. DSPy uses this to guide the LLM’s reasoning and tool usage.

Unlike traditional prompt engineering where you’d manage a complex string template, DSPy signatures are typed, declarative, and modular: you define the contract and DSPy handles the execution.

Structured Outputs: DSPy + Pydantic Validation

DSPy generates outputs based on the signature, but we add a second layer of validation with Pydantic. This two-stage approach separates concerns: DSPy handles LLM interaction, Pydantic enforces type safety and business rules.

Here’s our ComplaintResponse model:

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field, field_validator

class ComplaintResponse(BaseModel):

"""Structured output for complaint triage decisions."""

order_id: str

complaint_category: Literal["delivery_delay", "missing_items", "food_quality",

"service_issue", "billing", "other"]

decision: Literal["suggest_credit", "escalate"]

credit_amount: Optional[float] = None

confidence: Optional[Literal["high", "medium", "low"]] = None

priority: Optional[Literal["standard", "urgent"]] = None

rationale: str

@field_validator('complaint_category', mode='before')

@classmethod

def parse_category(cls, v):

"""Extract first valid category if multiple provided."""

if not isinstance(v, str):

return v

valid_categories = ["delivery_delay", "missing_items", "food_quality",

"service_issue", "billing", "other"]

v_lower = v.lower().strip()

# Exact match

if v_lower in valid_categories:

return v_lower

# Find first valid category in string

for cat in valid_categories:

if cat in v_lower:

return cat

return "other"

@field_validator('confidence', mode='before')

@classmethod

def parse_confidence(cls, v):

"""Ensure valid confidence value."""

if v is None or (isinstance(v, str) and v.lower() == "null"):

return None

if isinstance(v, str):

v_lower = v.lower().strip()

if v_lower in ["high", "medium", "low"]:

return v_lower

return "medium"

return v

@field_validator('priority', mode='before')

@classmethod

def parse_priority(cls, v):

"""Ensure valid priority value."""

if v is None or (isinstance(v, str) and v.lower() == "null"):

return None

if isinstance(v, str):

v_lower = v.lower().strip()

if v_lower in ["standard", "urgent"]:

return v_lower

return "standard"

return v

The validators handle edge cases gracefully. If the LLM returns “delivery_delay, food_quality” (multiple categories), parse_category extracts the first valid one. If it returns invalid confidence or priority values, the validators coerce them to valid defaults.

Beyond field-level validation, we wrap the agent’s execution in retry logic to handle cases where the LLM produces completely invalid outputs:

except (ValidationError, ValueError) as e:

if attempt < max_retries:

continue # Retry - DSPy will regenerate

else:

raise # Final attempt failed

If validation fails on the first attempt, DSPy regenerates the output, often correcting the issue. This simple pattern significantly improves reliability in production.

Unity Catalog Tools: Data-Driven Decisions

The agent’s decisions need to be grounded in real data. We use Unity Catalog SQL functions to retrieve order details, delivery timing, and location benchmarks. These functions are registered in UC and callable from the agent.

Here’s one example:

from unitycatalog.ai.core.base import get_uc_function_client

uc_client = get_uc_function_client()

def get_order_overview(order_id: str) -> str:

"""Get order details including items, location, and customer info."""

result = uc_client.execute_function(

f"{CATALOG}.ai.get_order_overview",

{"oid": order_id}

)

return str(result.value)

The agent also calls get_order_timing (to check delivery duration) and get_location_timings (to compare against location-specific percentiles). These tools turn vague complaints into data-backed decisions: “Your order was late” becomes “Order delivered in 87 minutes vs. P75 of 45 minutes → 25% credit justified.”

The ReAct Module: Orchestrating Tool Calls

DSPy’s ReAct module implements the Reasoning + Acting pattern: the agent iteratively reasons about the problem and calls tools to gather evidence.

Here’s how we set it up:

# Configure DSPy with your chosen model

lm = dspy.LM('databricks/meta-llama-3-1-70b-instruct', max_tokens=2000)

dspy.configure(lm=lm)

class ComplaintTriageModule(dspy.Module):

"""DSPy module for complaint triage with tool calling."""

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.react = dspy.ReAct(

signature=ComplaintTriage,

tools=[get_order_overview, get_order_timing, get_location_timings],

max_iters=10

)

When you call self.react(complaint="..."), DSPy:

- Reads the complaint and extracts the order ID

- Decides which tools to call (e.g., “I need delivery timing for this order”)

- Calls

get_order_timing(order_id)and receives results - Reasons about the results (e.g., “87 minutes vs. P75 of 45 minutes = significant delay”)

- Decides whether to call more tools or make a final decision

- Returns structured outputs matching the signature

DSPy makes this easy by handling all of the orchestration and translating our signatures into prompts for the model. All we really needed to do was define the signature and tools.

Tracing with MLflow

Observability is critical for agent development. MLflow’s autologging for DSPy captures execution traces automatically:

import mlflow

mlflow.dspy.autolog(log_traces=True)

With autologging enabled, every agent invocation produces a trace showing:

- Tool calls made (which functions, with what arguments)

- Tool outputs (actual data returned)

- Reasoning steps (how the agent synthesized evidence)

- Final decision and rationale

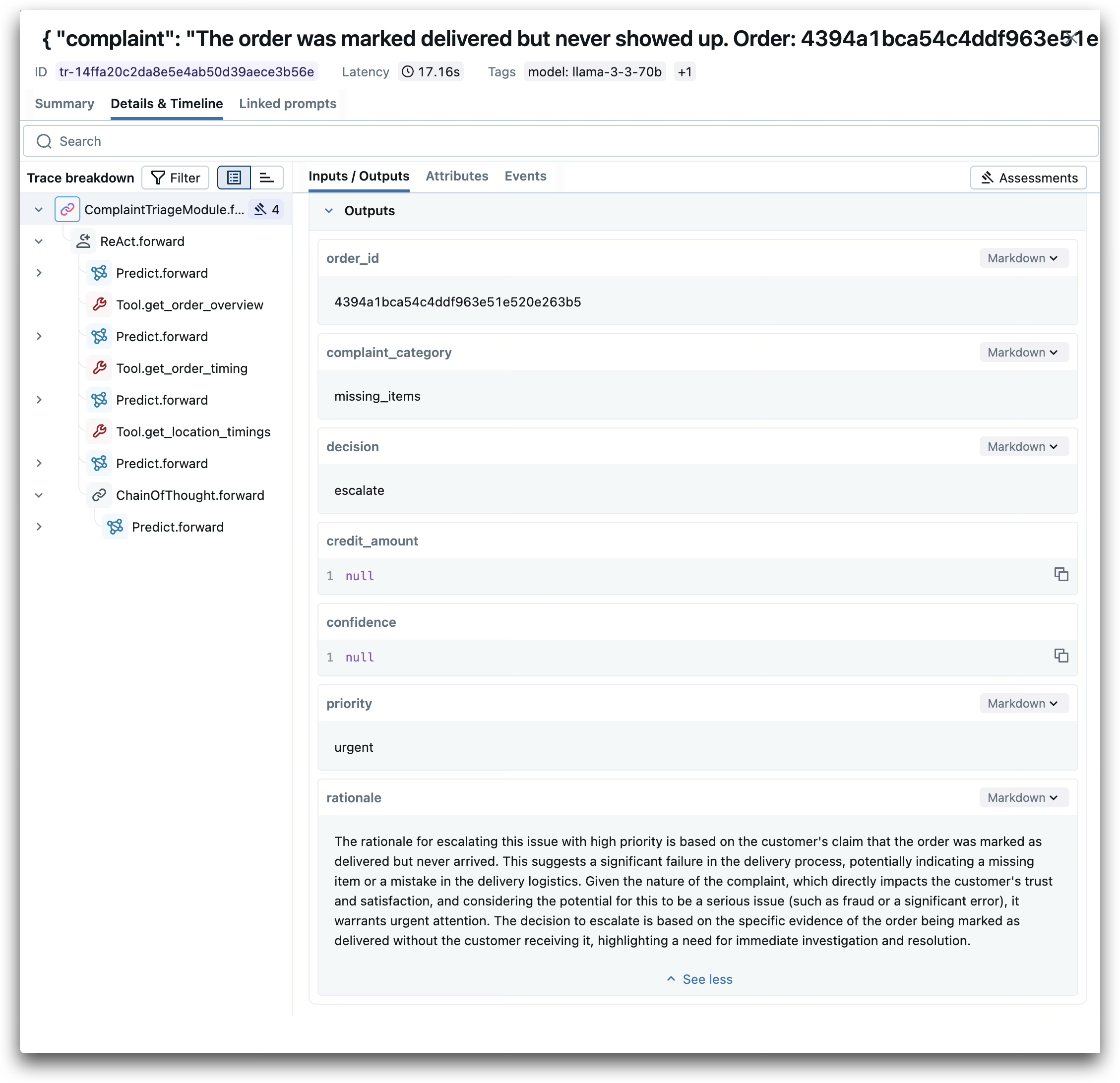

Here’s an example trace from our agent:

These traces are invaluable for debugging (“Why did the agent escalate this?”), evaluation (“Does the rationale match the tool outputs?”), and iteration (“Which tools does the agent use most?”). They also become the foundation for systematic evaluation: by comparing agent decisions and rationales against tool outputs across a dataset of complaints, we can quantify quality and identify where the agent needs improvement.

Seeing It in Action

Here’s a real example from the MLflow trace shown above. The complaint:

The order was marked delivered but never showed up. Order: 4394a1bca54c4ddf963e51e

The agent made three tool calls to gather evidence:

get_order_overview- Retrieved order details and itemsget_order_timing- Checked delivery timestampsget_location_timings- Fetched location-specific benchmarks for context

Based on this evidence, the agent decided to escalate with urgent priority. This follows directly from the Decision Framework embedded in the agent’s signature: complaints about orders marked delivered but never received suggest potential fraud or significant logistics failures—cases that warrant urgent human review rather than automated resolution.

The agent’s rationale explains its reasoning clearly, citing the specific evidence (order marked as delivered without customer receipt) and justifying why urgent attention is warranted. This isn’t arbitrary—it’s following the rules we defined in the signature, applied to real data retrieved from Unity Catalog functions.

This is exactly what we need at scale: consistent triage that uses real order data to make fair, explainable decisions.

Deployment and Beyond

Once the agent works reliably in development, deployment is straightforward. We wrap the DSPy module in an MLflow ResponsesAgent for compatibility with Databricks Model Serving:

from mlflow.pyfunc import ResponsesAgent

from mlflow.types.responses import ResponsesAgentRequest, ResponsesAgentResponse

class DSPyComplaintAgent(ResponsesAgent):

def __init__(self):

self.module = ComplaintTriageModule()

def predict(self, request: ResponsesAgentRequest) -> ResponsesAgentResponse:

complaint = request.input[0]["content"]

result = self.module(complaint=complaint)

return ResponsesAgentResponse(

output=[self.create_text_output_item(text=result.model_dump_json())]

)

We log the model with MLflow, register it in Unity Catalog, and deploy to a serving endpoint. Production traces flow to a dedicated MLflow experiment for monitoring. The full deployment workflow is in this notebook.

MLflow also enables rigorous evaluation and model comparison. In this companion notebook, we evaluate the same agent architecture across multiple models (Claude, GPT, Llama) to find the best balance of quality, latency, and cost—all without changing the core agent code.

Wrapping Up

Building reliable agents requires more than good prompts. You need structured outputs, data-driven reasoning, robust error handling, and observability. DSPy and Databricks provide the tools to achieve all of this with relatively concise, composable code.

For Casper’s Kitchens, this agent transforms complaint triage from a manual, subjective process into an automated, evidence-based one. Every decision is grounded in real order data. Every response includes a clear rationale. And every execution is traced and evaluable.

The patterns here generalize beyond complaint triage. Wherever you need agents that call tools, return structured outputs, and make decisions based on real data, DSPy’s approach offers a clean path forward.

About Casper’s Kitchens

Casper’s Kitchens is an end-to-end demo project showcasing AI and data engineering patterns on Databricks. Built around a fictional ghost kitchen network, it demonstrates streaming data pipelines, agent development, model evaluation, and production deployment workflows. The complaint triage agent is one component in a larger system that includes refund recommendation, data quality monitoring, and reverse ETL—all designed to illustrate real-world patterns you can adapt for your own use cases.

Explore the code:

- Complaint Agent Notebook: Full implementation with deployment

- Model Comparison Notebook: Evaluating multiple models

Learn more: